on statistics

May 8

May 8th, 2018

sidenote: This post is based entirely on what I’ve learned while reading ^that book.

Three concepts in statistics that are important to understand.

1. Law of Large Numbers

“An important theorem known as the law of large numbers tells us that as the number of trials increases, the average of the outcomes will get closer and closer to its expected value”

This is counter intuitive. This is how I think of this theory.

You are flipping a coin 10 times. Imagine the first eight times you flip the coin, it lands on heads. Intuitively, you would assume that the next flip is more likely to land on tails than heads. This is FALSE.

Every time you flip the coin, nothing different is happening. Every flip is a 50/50 chance.

At the end of your 10 flips, you have landed nine heads and one tail. This doesn’t make sense. If the likelihood of flipping both possibilities is equal, why is the outcome so skewed?

This is because you have witnessed an anomaly. The chances of you hitting nine heads in a row are very small (1/512 or 0.2%). The results you have witnessed are not representative of the true probability.

The true probability only emerges as you keep flipping the coin.

The logic behind this is hard to understand.

Basically, the more time you flip the coin, the less anomalies (like nine heads in a row) will matter to the overall result. Eventually anomalies are drowned out and the true probability can be seen.

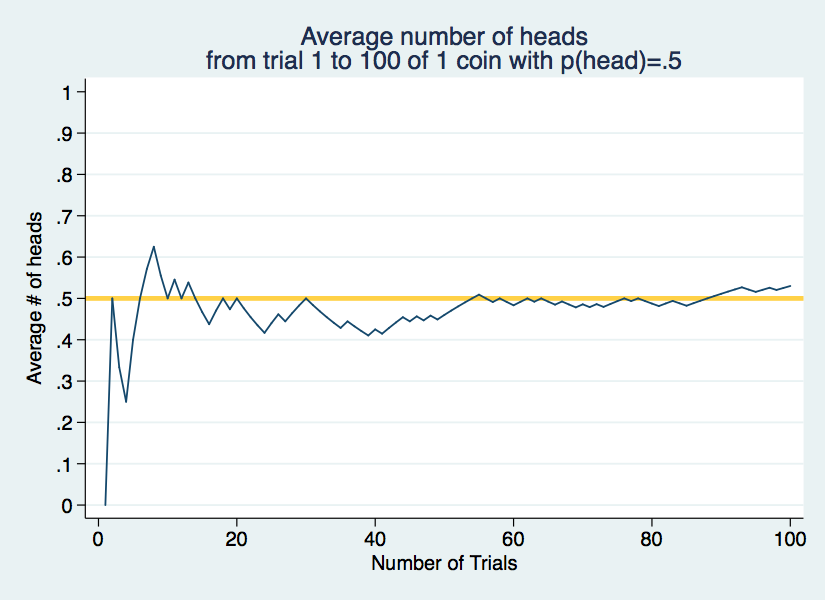

The chart below illustrates the theory. Every flip, the average of heads is calculated: (number of head flips / total number of flips). According to everything that makes sense, that number should be 0.5 or 1/2.

Over the first 10 trials, the average number of heads fluctuates wildly, from an underrepresentation to an overrepresentation in 10 flips. You can see how if we stopped after just 10 flips, it would be hard to draw a conclusion about the true probability of this situation.

As more coins are flipped though, the average number of heads move closer to 0.5, which is what probability says it should be.

“The law of large numbers explains why casinos always make money in the long run. The probabilities associated with all casino games favor the house (assuming that the casino can successfully prevent blackjack players from counting cards). If enough bets are wagered over a long enough time, the casino will be certain to win more than it loses.”

Wheelan, Charles. “Naked Statistics: Stripping the Dread from the Data.”

2. Independent and Dependent Relations

Every time a coin is flipped heads, the chance of the second flip being heads stays exactly the same. This is called an independent relation.

Every time a car is parked, the chance of the driver getting a parking ticket increases. This is a dependent relation.

Often, we do not realize what events are independent and dependent.

The classic example is a “hot-hand” in basketball. After a player makes a certain amount of shots in a row, it seems more likely that he will make the next shot. We assume that this is a dependent relation.

3. Percentages

More often than not, a percentage is a better way to understand data than an absolute number.

When looking at a storefront, I would rather know what percentage of the price is discounted than an absolute number. Saving $5 on a $10 item is awesome, but saving $5 on a $2000 item is almost irrelevant.

When looking at a company, I would rather know a percentage for revenue growth rather than an absolute number. Growing yearly revenues from $20 billion to $20.1 billion is not a huge difference, but $100 million in additional revenue sounds great.

Percentages give you context for absolute numbers.

Therefore, we should address some fallacies.

1.

“Assume that a department store is selling a dress for $100. The assistant manager marks down all merchandise by 25 percent. But then that assistant manager is fired…and the new assistant manager raises all prices by 25 percent. What is the final price of the dress? If you said (or thought) $100, ”

Then you are wrong. Here is what happened.

The price was originally $100. Then it was discounted by 25%.

25% of $100 is, clearly, $25. Therefore, the new price is $100 - $25 = $75.

Then the price was raised by 25%.

25% of $75 is $18.75. Therefore, the new price is $75 + $18.75 = $93.75.

This concept is especially important in the stock market:

Say you buy $50 of Apple stock on Monday. The stock goes down 12% on Tuesday, but then goes up 12% on Wednesday. You do not start Thursday with $50 of Apple stock. You will have less.

2.

“The Democrats, who engineered this tax increase, pointed out (correctly) that the state income tax rate was increased by 2 percentage points (from 3 percent to 5 percent). The Republicans pointed out (also correctly) that the state income tax had been raised by 67 percent.”

This example

Luck versus Skill in the Cross-Section of Mutual Fund Returns

this post is incomplete